CHRISTMAS is not what it was. But then, perhaps, it never has been. The fear that we have lost something — that, somehow, our Christmas celebrations are lacking some quality, whether piety, authenticity, or genuine enthusiasm — is almost as old as the commemoration of Christmas itself.

As early as 380, St Gregory of Nazianzus was able to assemble an ample list of ways in which the festival was being debased. “Let us not”, he exhorted his readers, “adorn our porches, nor arrange dances, nor decorate the streets; let us not feast the eye, nor enchant the ear with music, nor enervate the nostrils with perfume, nor prostitute the taste, nor indulge the touch.”

The anxiety that the real meaning of Christmas has been abandoned in a welter of gaudy, even sinful, distractions has never gone away. This year, we will undoubtedly hear it articulated again; indeed, such complaints are almost as much a part of modern Christmas tradition as roast turkey and a family row about the real rules of Monopoly. But, since at least the 16th century, there has been an alternative fear: the disquieting belief that, far from promoting excessive celebration, the old idea of Christmas spirit and Yuletide cheer has been forgotten.

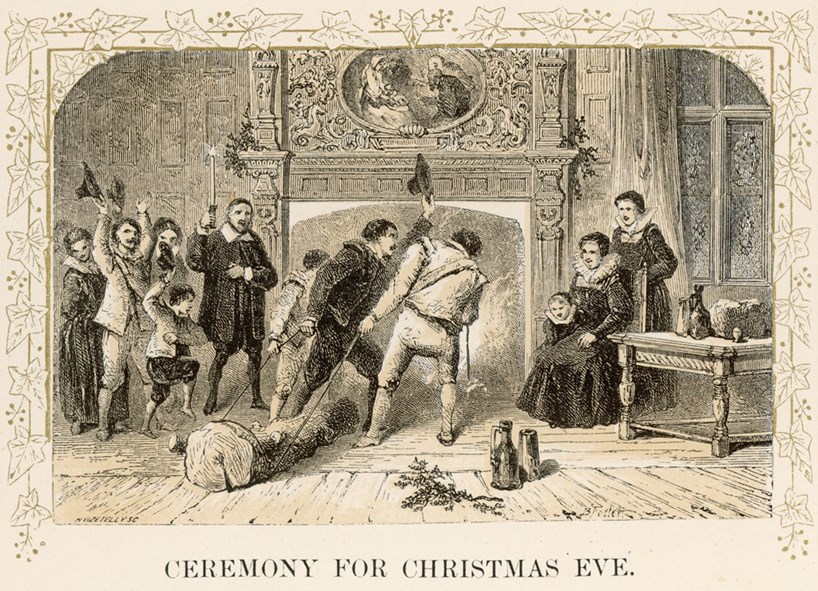

Such angst can be discerned in the many complaints of early modern writers that the immemorial traditions of Christmas hospitality had been abandoned. It was also the spur for King James I and VI’s extraordinary injunctions of the 1620s, when he insisted that the gentry leave London for their country homes at Christmas to preside over provincial celebrations. In what the historian Felicity Heal calls “a whirlwind of confusion”, no fewer than 7000 families in 1400 coaches were thus forced out of the capital just before Christmas in 1622.

Both puritanical and nostalgic, conscious of their great material advantages and ceaselessly uneasy about their presumed spiritual decline, British people in the 19th century inherited all this unease. At one and the same time, and often in the same text, contemporary writers decried the superficiality and excess of contemporary Christmases, while also bemoaning their failure to live up to the expansive, even lavish, traditions of the olden times. As Clare Simmons points out in her recent study of the subject, they read and frequently quoted the words of Sir Walter Scott, not least his long poem of 1808, Marmion, A Tale of Flodden Field.

In it, Scott attempted to reconcile Christmas and Yule, pure faith and bodily enjoyment, showing that each was an aspect of the other. With Christmas bells in church and Christmas food at home, Scott depicted an idealised festival, set in an imagined past where “Domestic and religious rite Gave honour to the holy night”:

England was merry England, when

Old Christmas brought his sports again.

’Twas Christmas broach’d the mightiest ale;

’Twas Christmas told the merriest tale;

A Christmas gambol oft could cheer

The poor man’s heart through half the year.

His was a voice that spoke to an anxious age.

WRITING in 1820, the American author Washington Irving was equally vociferous and just as influential in both celebrating Christmas past and regretting Christmas present. The English, he bemoaned, “were, in former days, particularly observant of the religion and social rite of Christmas”.

Now, he went on, although the season remained important, “the world has become more worldly. There is more of dissipation, and less of enjoyment.” The ancient traditions, which “brought the peasant and the peer together”, were “daily growing more and more faint, becoming gradually worn away by time, but still more obliterated by modern fashion”.

Artists, perhaps even more than authors, contributed to this sense of falling off from some imagined past — and no one more so than the Irish painter Daniel Maclise, whose Merry Christmas in the Baron’s Hall was greeted rhapsodically on its unveiling in 1838. “He is beating us all,” Edwin Landseer observed; “his imagination, grouping, and drawing is wonderful.” Packed with activity, Maclise’s canvas depicts feasting and singing and laughing; at the front, one ebullient group plays hunt the slipper. It is an image of pure celebration, but also an implicit critique of contemporary Christmases.

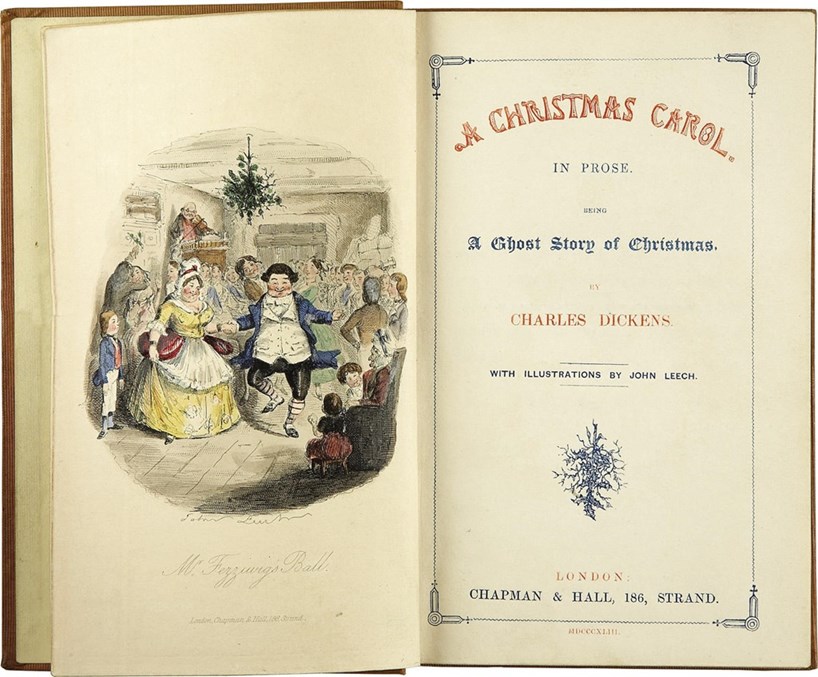

AlamyTitle page and frontispiece of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1843)

AlamyTitle page and frontispiece of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1843)

It was in this context that our modern Christmas was invented: the product of apprehension as much as celebration. The Victorians are often — and rightly — seen as great innovators when it comes to Christmas. In the year 1843 alone, Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol, and Henry Cole created the first-ever Christmas card. The festive season would never be quite the same again.

Yet it is striking just how much of this invention was depicted as revival, and how often it was justified as the re-creation of older, better times. Cole used antiquated spelling in signing his card “Xmasse”. Dickens likewise revived the figure of Father Christmas, and sought to recall his readers to a lost world of “Merry England”: precisely the England that others mourned. We know that Dickens read Scott and Irving; he was also a close friend and admirer of Maclise, who painted his portrait in 1839 and created illustrations for many of his Christmas books.

CHURCHES shared this sense of loss. Preoccupied by the religious temper of the age, fretful about the state of society, and sharing that profound nostalgia for what they believed had been lost in the march of progress, both clergy and laity drew on the past in hope of improving the present and imagining a better future.

How this shaped worship can be seen in the writings of the journalist, spiritualist, and disillusioned Tractarian priest Charles Maurice Davies. In the 1870s, he toured the churches of London, producing a series of books exploring contemporary religious life. What he found was a world in flux, as an attempt to revive older ideas produced a series of lasting changes.

AlamyTapioca for sale in the window of Quick & Sons, Chiswick, c.1905

AlamyTapioca for sale in the window of Quick & Sons, Chiswick, c.1905

On Christmas Eve 1874, for example, he witnessed good Evangelical churches “which never knew a floral device or blazoned a cross on their walls” infected by the fashion for neo-medieval symbolism. “I saw one such,” he wrote, “where a dear Conservative old parish clerk was moaning and groaning like Mrs Gammage herself because a young lady had brought the sacred emblem wrought in green and camellias by her fairy fingers, and the minister was putting it up with his own reverend hands. To his bewildered mind it was the closing in of a dispensation.”

Travelling round the metropolis, Davies found few exceptions. “Even extreme Broad Church has caught the contagion,” he commented. The effect was such that the churches invented new forms of worship, as they attempted to recreate something of the old idea of Christmas. In 1873, Davies seized on the “crib service” as an innovation — though one, happily, confined only to Roman Catholic communities. Horrified by “wax figures decidedly the worse for wear” in one church, and by “a wisp of straw, a cheap doll with uncomfortably scanty shirt, two Christmas trees, and a Child’s night-light” at another, Davies rejoiced that no Anglicans had yet been enticed to imitate this unwelcome development. He rather doubted that they ever would be.

Davies was wrong, of course. That particular revival could only grow in popularity. But other changes happily proved more ephemeral. Once again seeking to revive something of the symbolism of the past, Christmas Day at St Paul’s, Hammersmith, in 1874, brought “a splendid cross of white feathers, with the word ‘Alleluia’ on a crimson scroll”. More remarkably still, “The texts on the windows were made out of most unlikely material — namely, tapioca.” There were flowers round the font and wreaths on the reading desk. “Who”, Davies asked, “will say, after this, that our Church Establishment is not exhaustive and capable of assimilating the most unexpected elements?”

AlamyBringing in the yule log: a scene of Jacobean England imagined by the 19th-century illustrator Henry Vizetelly (1820-94)

AlamyBringing in the yule log: a scene of Jacobean England imagined by the 19th-century illustrator Henry Vizetelly (1820-94)

Curiously, the picture that Davies paints is both familiar and unsettling. He depicted as a novelty things that we now take for granted, whether the crib service or special Christmas flowers. More important, in figures such as the “dear Conservative old parish clerk”, he showed those who saw change as a falling away, while the “young lady” with her floral display represented others who hoped to recover something of the spirit of Christmas past.

The Victorians, in that sense, were much more than just the inventors of the modern Christmas. They did, indeed, bequeath to us a set of practices, assumptions, and ways of worshipping which we now regard as traditional. More significantly, though, their experience — like ours — shows a persistent problem with how people approach Christmas. The Victorians were inheritors and promulgators of a long-standing tradition of concern about the celebration. Like us, they feared that something essential had, in some way, been lost.

Filled with nostalgia, worried about change, often inclined to believe that things were better back in the day, we, too, are in danger of failing to appreciate what we have now. It is easy to feel that we are failing. The festive season is often filled with regret or disappointment. But Christmas is, in truth, a miracle every year. And this year, more than most, we need to remember that.

The Revd Dr William Whyte is Fellow and Tutor of St John’s College, Oxford, and Professor of Social and Architectural History in the University of Oxford.